CURATED BY

Julia Pollack

WHEN

April 12 - April 12

WHERE

Cafeteria & Company

View Gallery

1

/

10

1 / x

EIDOLON OF ORPHEUS

This year’s exhibit is the study of Nature’s mysteries. All scientists stand at the edge of a precipice; behind them is the accumulated knowledge of their peers and preceptors and in front of them lies a fog of questions. As they cast out the torch of scientific inquiry, the fog either dissipates to reveal clear answers or thickens, leaving more questions.

As Walt Whitman said in his poem “Eidolons”:

Beyond thy lectures learn’d professor,

Beyond thy telescope or spectroscope observer keen, beyond all mathematics,

Beyond the doctor’s surgery, anatomy, beyond the chemist with his chemistry,

The entities of entities, eidolons.

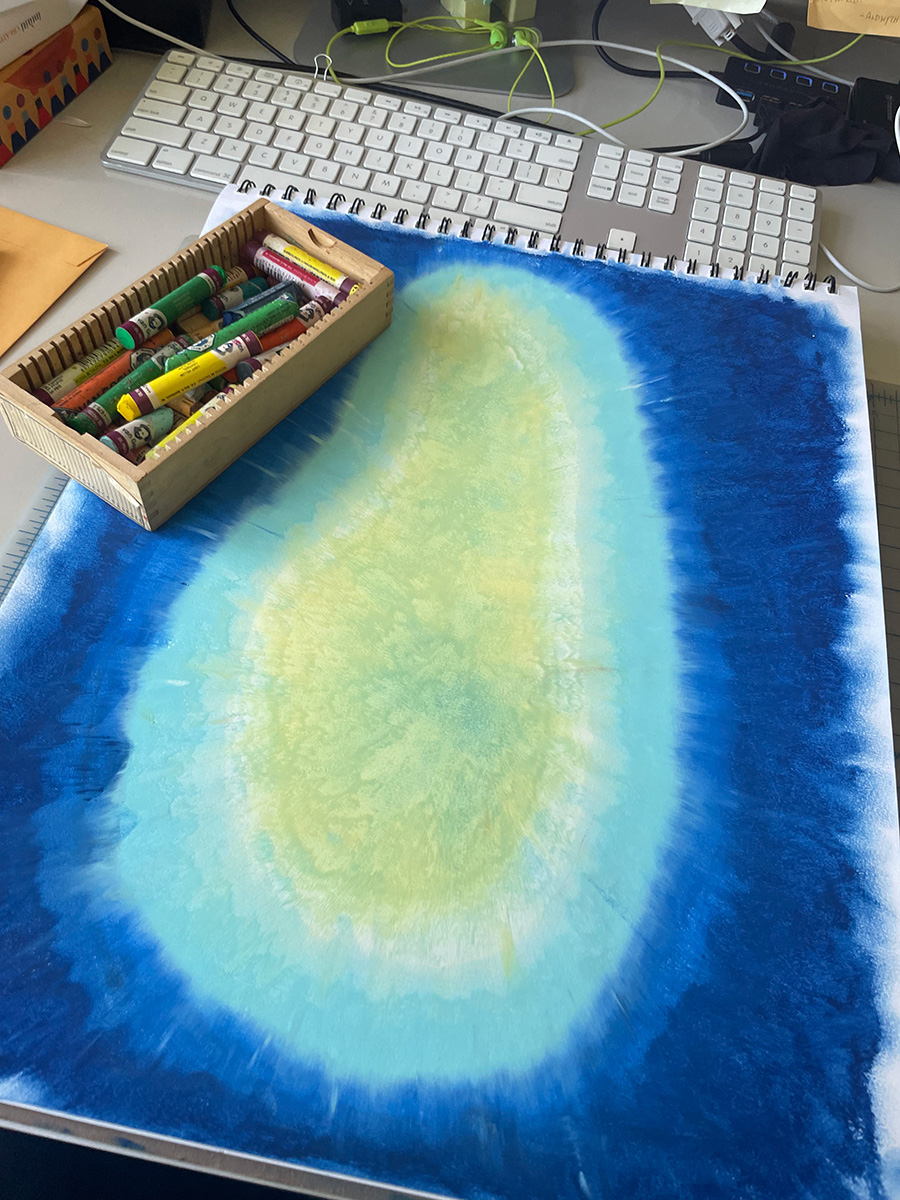

The colorful layers of the image were created from oil pastel drawings and serve as a background to the mold Penicillium, which is central to the production of delicious cheeses, industrial enzymes, and, famously, the antibiotic penicillin. Usually, you might see this fungus as an offensive, dark piece of velvet cloth growing on rotten fruits. If you zoom in using a microscope, however, a different picture emerges; a branching tree whose individual units indelibly changed the landscape of medicine.

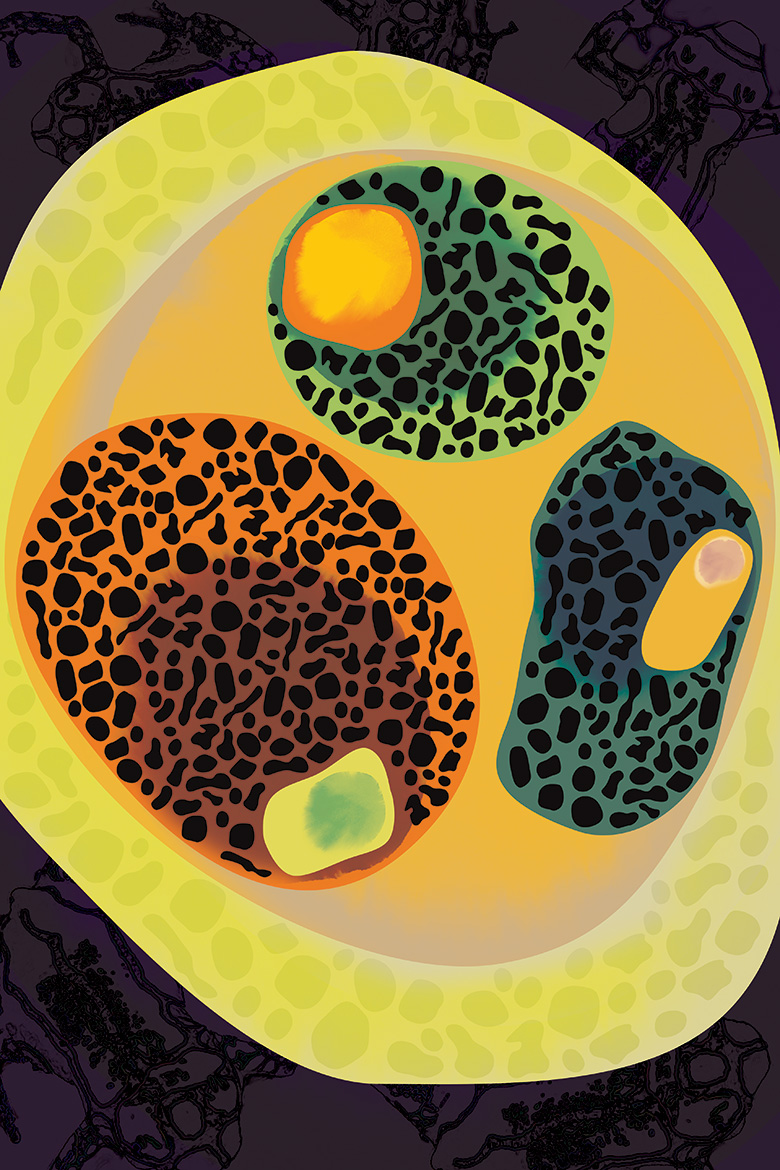

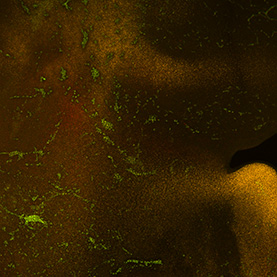

COLLIDOSCOPE

As a society, humans have always been intrigued

by X-ray vision, which allows one to see through normally opaque objects. The fascination with this ability has made its way into Greek mythology, in the form of the Argonaut Lynceus, and modern comics, like Superman. Both heroes have been described as having excellent sight, enabling them to see through the ground, walls, and skin. In reality, this phenomenon has been harnessed for a variety of applications, including security checks and medical diagnostics. However, X-rays can only be used to image bones, begging the question: What happens when scientists want to look at other living tissues?

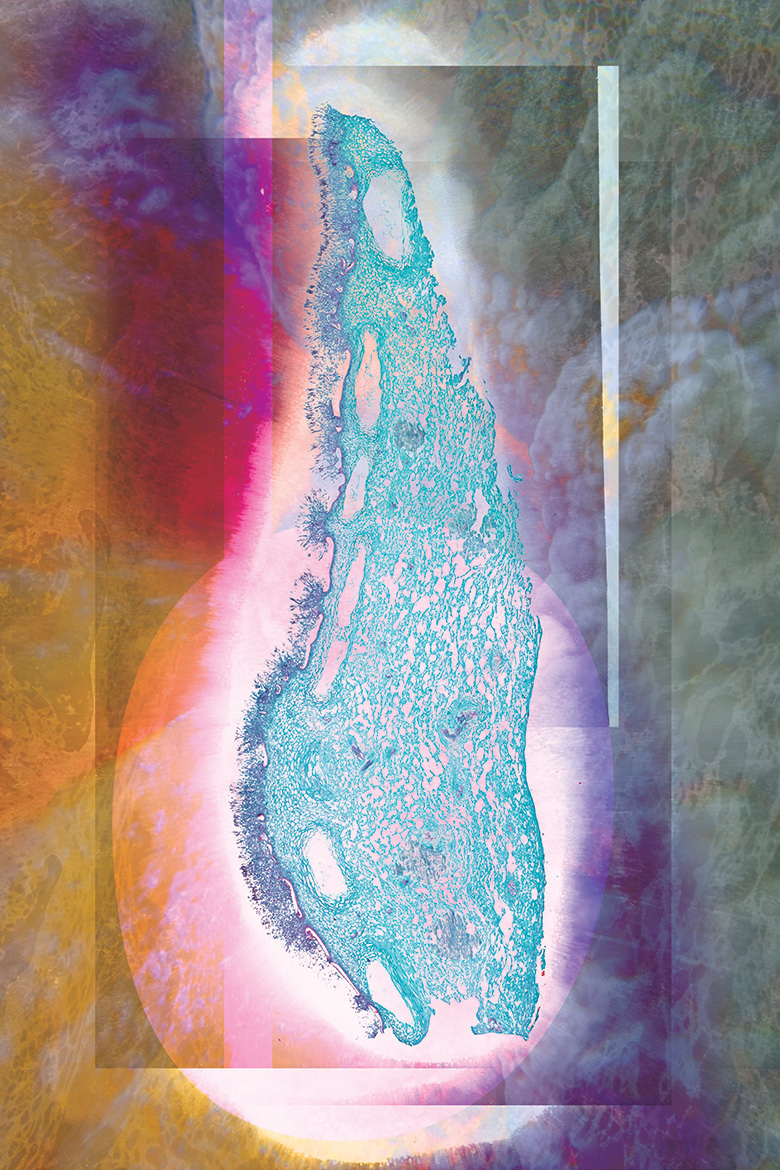

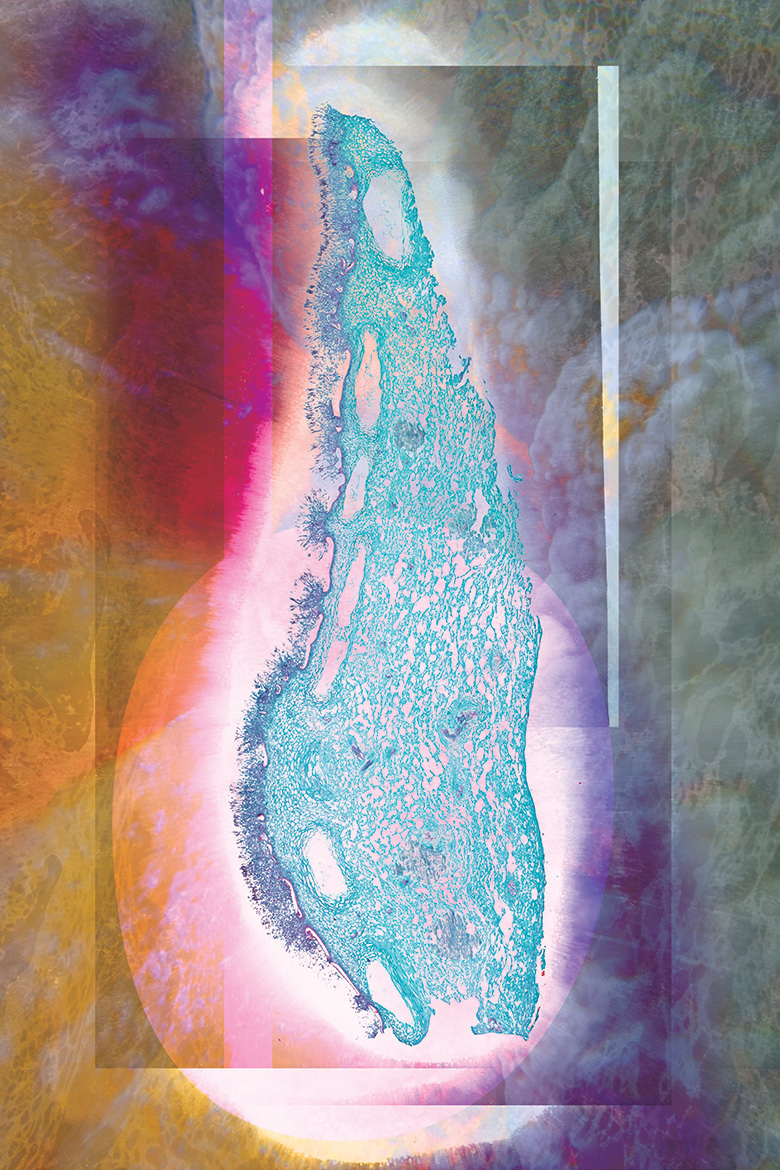

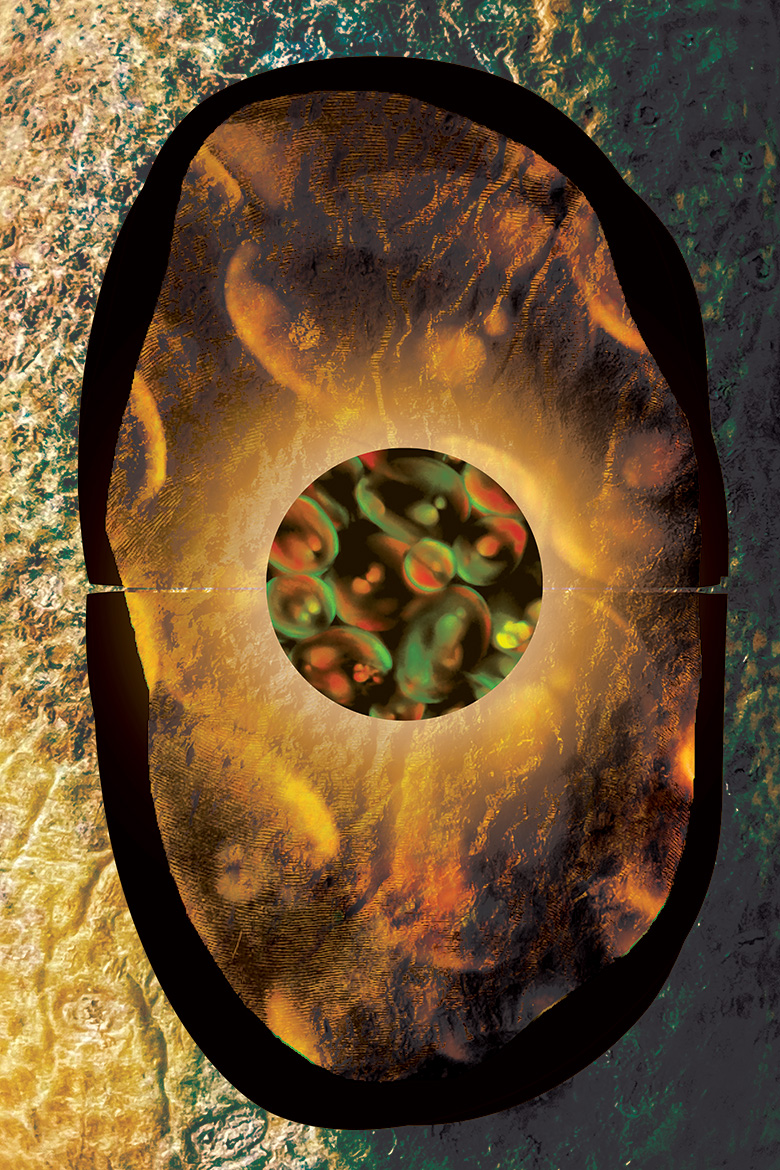

There is a growing need for label-free imaging which allows researchers to peer into the body of plants, animals, and humans without damaging them. One such method is second-harmonic imaging, which takes advantage of the fact that molecules scatter light in distinct ways. In this image, the outer layers of the starch granules in a potato slice, green, can be distinguished from the inner red core. The resulting piece is an homage to different imaging techniques: ink drawings, photographs, and microscope images.

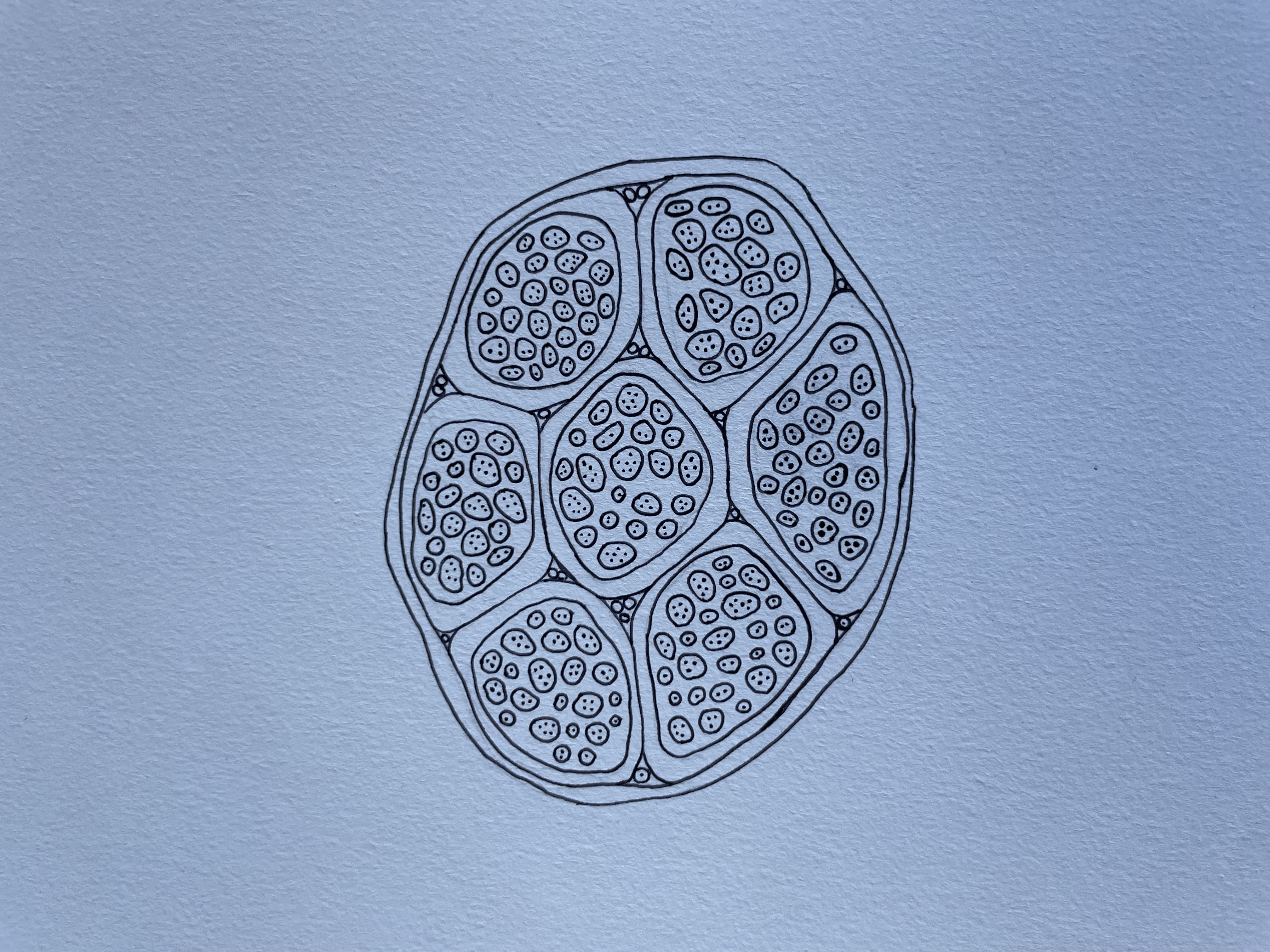

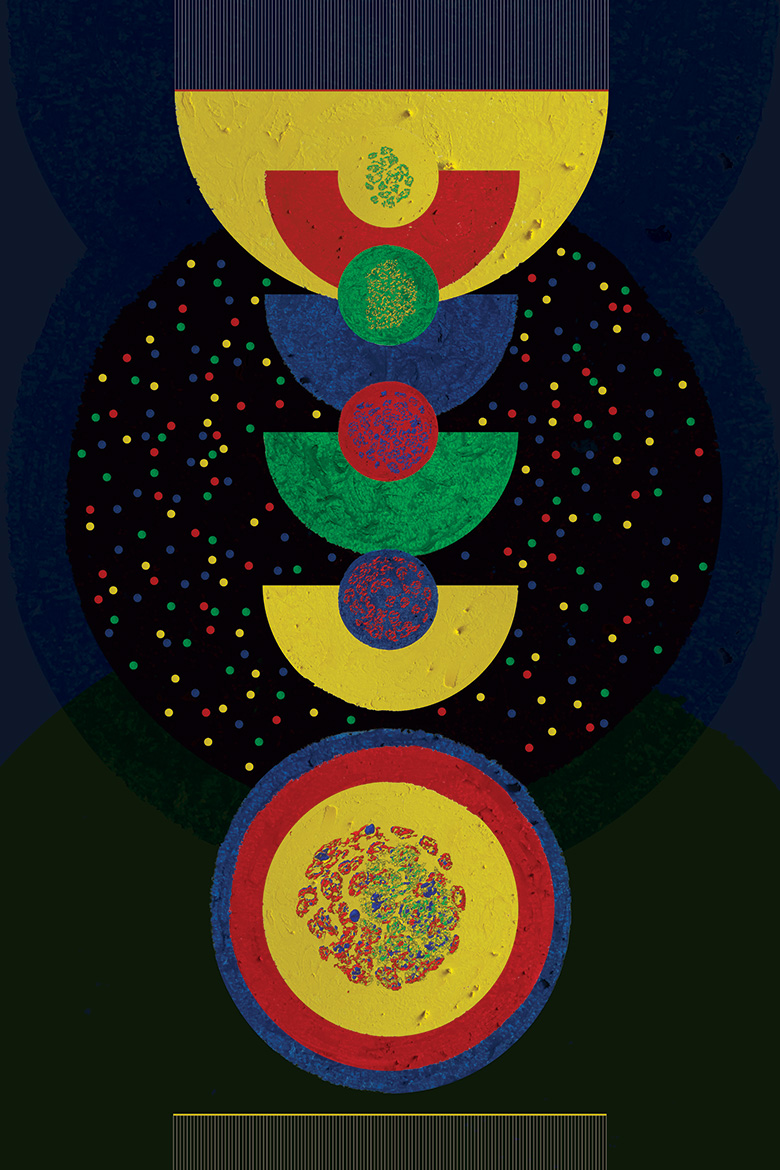

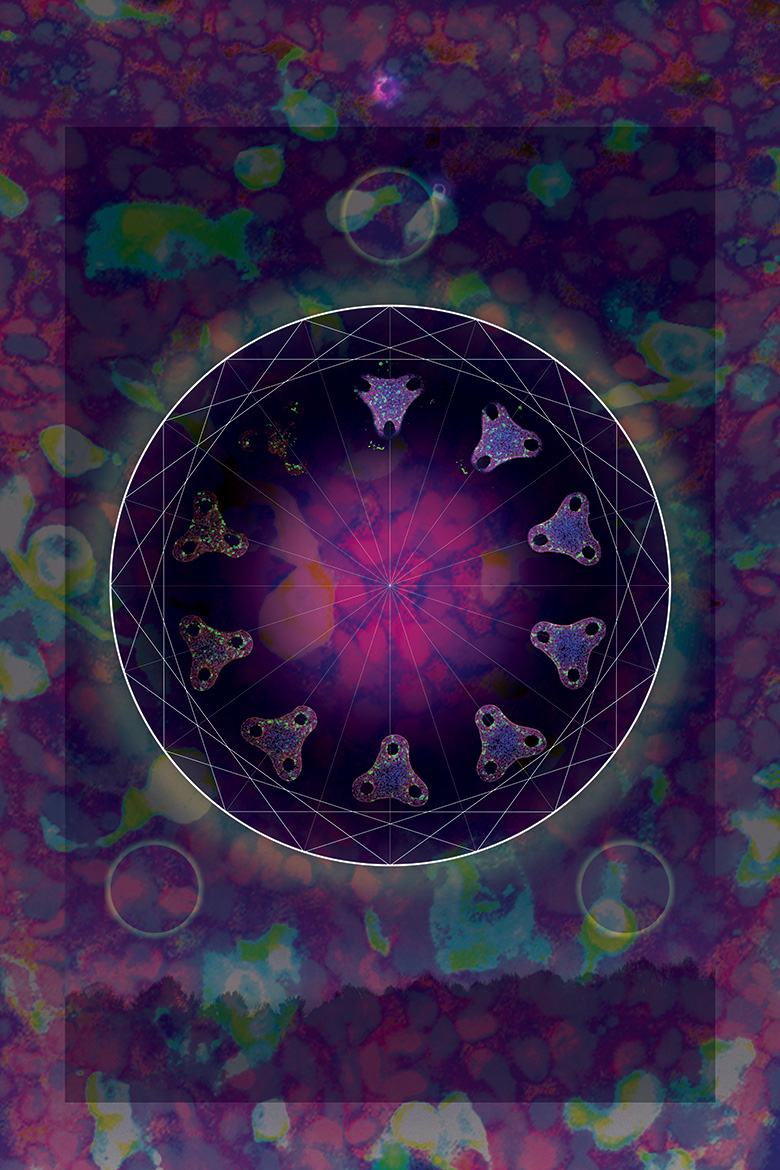

CYLCH

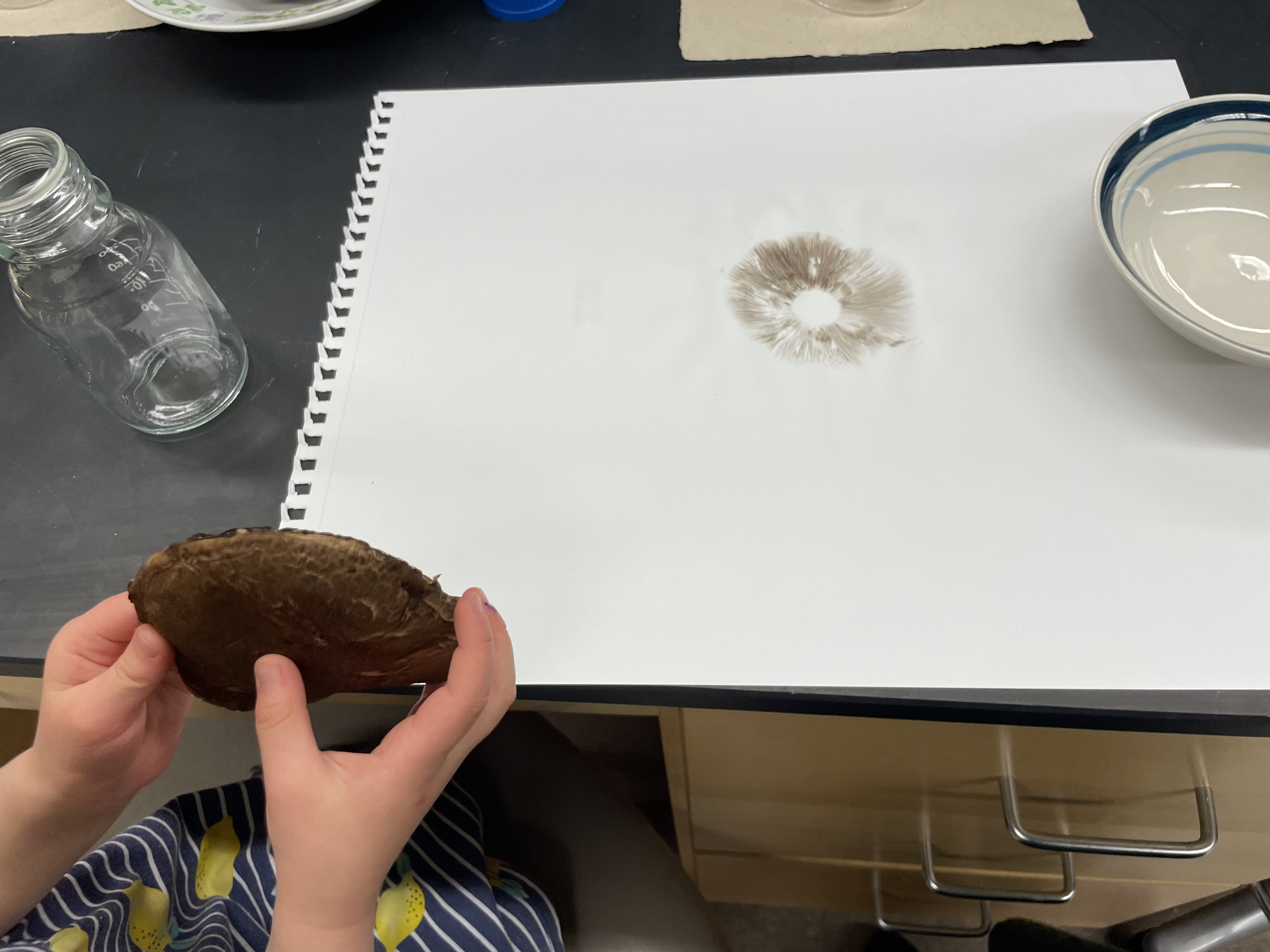

The Tree of Life is a ubiquitous archetype in many mythological and religious traditions, including the eponymous tree of life in Judaism and Christianity; Kalpavriksha in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism; and Yggdrasil in Norse mythology. Usually, the tree is protected by supernatural custodians in a sacred garden or forest and is a bridge between heaven and earth. It should come as no surprise, then, that in ancient mythology, mushrooms represented the fruiting body of this tree and were believed to either confer longevity and good health or serve as a portal to the fairy realm.

The artist captures these beliefs by layering prints of mushroom spores with microscopy images of mushroom cross-sections. The result is a three-part hierarchical structure: at the base is the stalk of the mushroom that anchors it to the earth’s energy, the center is a gateway for fairies as they dance between our world and theirs, and the peak is the promise of eternal life.

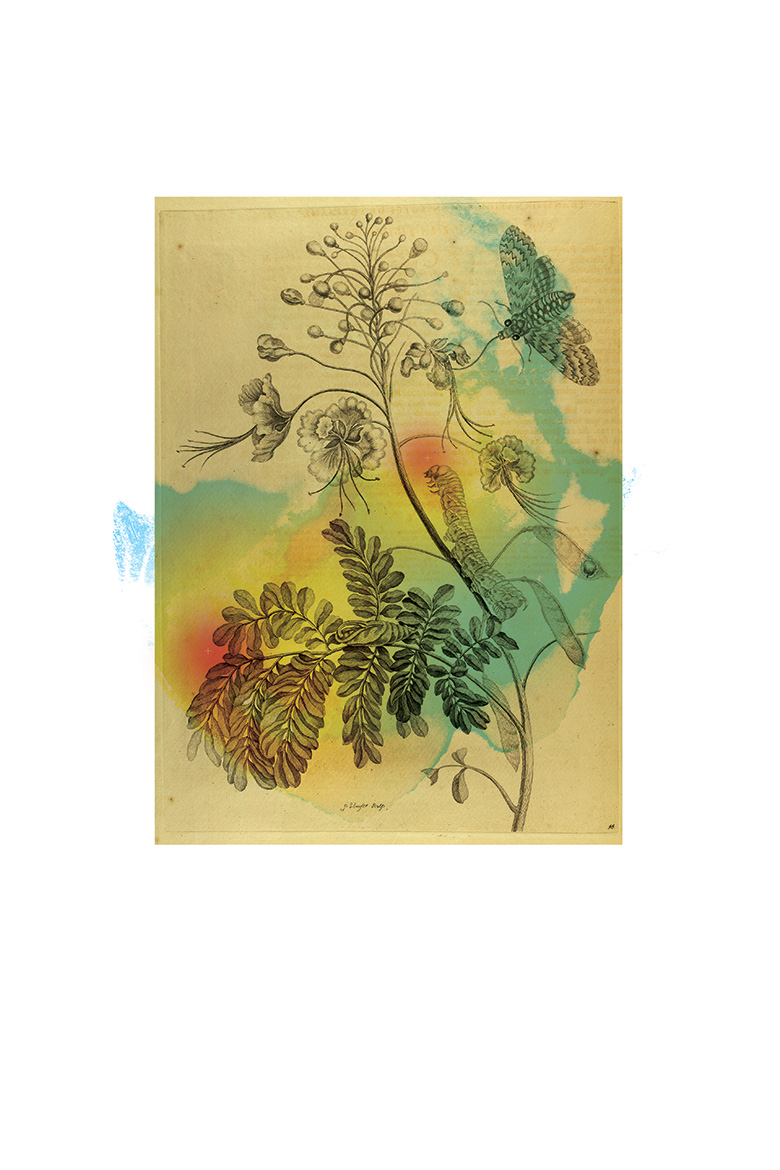

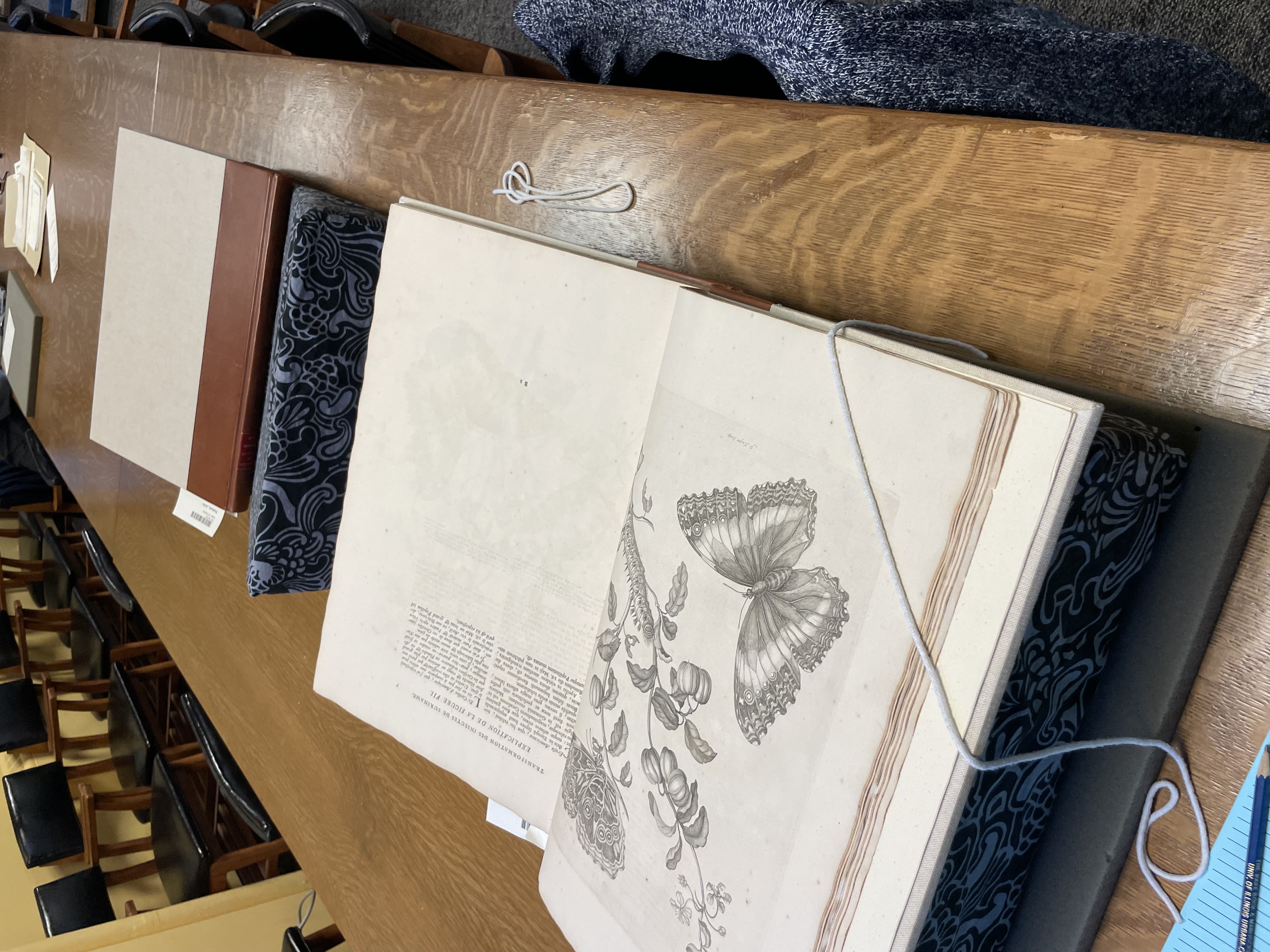

EHECACHICHTLI

The smell of freshly-cut grass heralds the onset of summer, triggering memories of vacations and picnics. For plants, however, these smells are alarm calls that danger is afoot. The immobility of plants has induced them to create unique signals that help them warn each other about predators. These signals, called volatile organic compounds, are akin to perfume sprays that attract, for example, insects that swoop down on the plants and feed on predatory caterpillars. Consequently, insects that are flying over a field can pick out a single plant that is essentially lit up like a billboard, announcing the availability of lunch.

The two pieces are a nod to how far the field of entomology has progressed over the past 2000 years. Initial studies involved describing insects through drawings as seen in the print by Maria Sibylla Merian, a German entomologist and scientific illustrator. The original copy from the 1700s can be found at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois. The artist has treated the scan with ink stains and color blotches to highlight the volatile compounds that plants cast out into their environment. The paired image is a hornworm caterpillar on a tomato leaf surrounded by a color-inverted ink stain. The compounds have been highlighted to convey that researchers are still studying them to understand the full range of plant communication. Together, the pieces emphasize that the idyllic images we associate with nature are often combat zones, ripe with intrigue and deception.

EHECACHICHTLI

The smell of freshly-cut grass heralds the onset of summer, triggering memories of vacations and picnics. For plants, however, these smells are alarm calls that danger is afoot. The immobility of plants has induced them to create unique signals that help them warn each other about predators. These signals, called volatile organic compounds, are akin to perfume sprays that attract, for example, insects that swoop down on the plants and feed on predatory caterpillars. Consequently, insects that are flying over a field can pick out a single plant that is essentially lit up like a billboard, announcing the availability of lunch.

The two pieces are a nod to how far the field of entomology has progressed over the past 2000 years. Initial studies involved describing insects through drawings as seen in the print by Maria Sibylla Merian, a German entomologist and scientific illustrator. The original copy from the 1700s can be found at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois. The artist has treated the scan with ink stains and color blotches to highlight the volatile compounds that plants cast out into their environment. The paired image is a hornworm caterpillar on a tomato leaf surrounded by a color-inverted ink stain. The compounds have been highlighted to convey that researchers are still studying them to understand the full range of plant communication. Together, the pieces emphasize that the idyllic images we associate with nature are often combat zones, ripe with intrigue and deception.

LES SANGLOTS LONGS DES VIOLONS

The beginning of spring is usually marked by concerts of different bird calls, signifying the end of a dreary winter season and the birth of new life. What sounds delightful to us, however, is sometimes an alarm that warns of insidious invaders. The ability to build a nest is what separates birds from most of the animal kingdom. However, some birds, like the brown-headed cowbird, don’t know how to make one and instead lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. The unwilling hosts, such as yellow warblers, have to spend time and energy taking care of these encroachers. As a response, these animals have evolved a unique “seet” call that alerts nearby warblers to the presence of cowbirds.

This conflict is portrayed through flattened forms and decorative patterns that are reminiscent of the work of Henri Matisse, a French visual artist. The highlighted standoff between the cowbird and the yellow warbler elevates the sense of drama–on one hand, the cowbird is adamant that its offspring receives the best care, and on the other, the indignant warbler sends out a war cry to its friends warning them to keep their guard up.

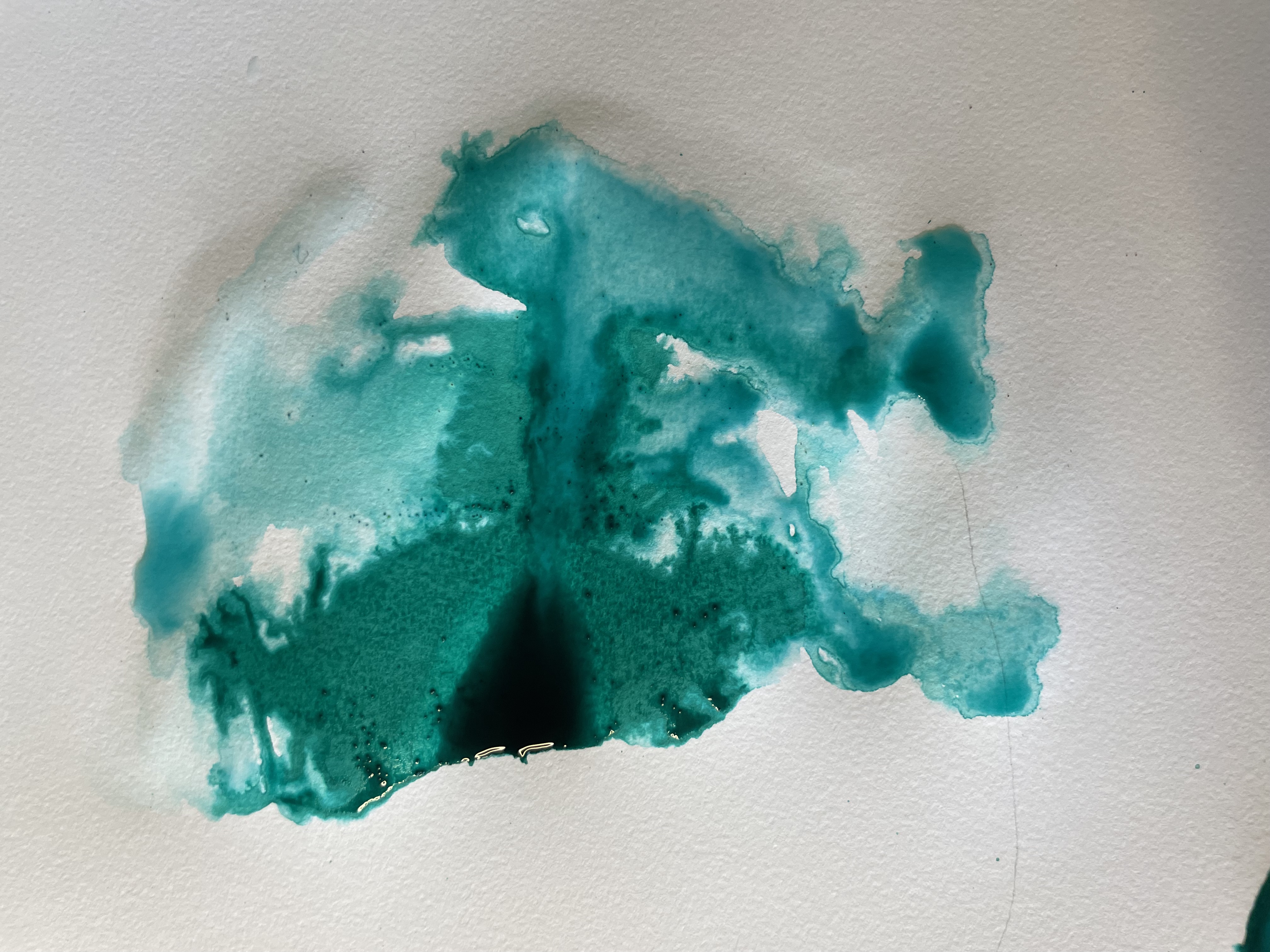

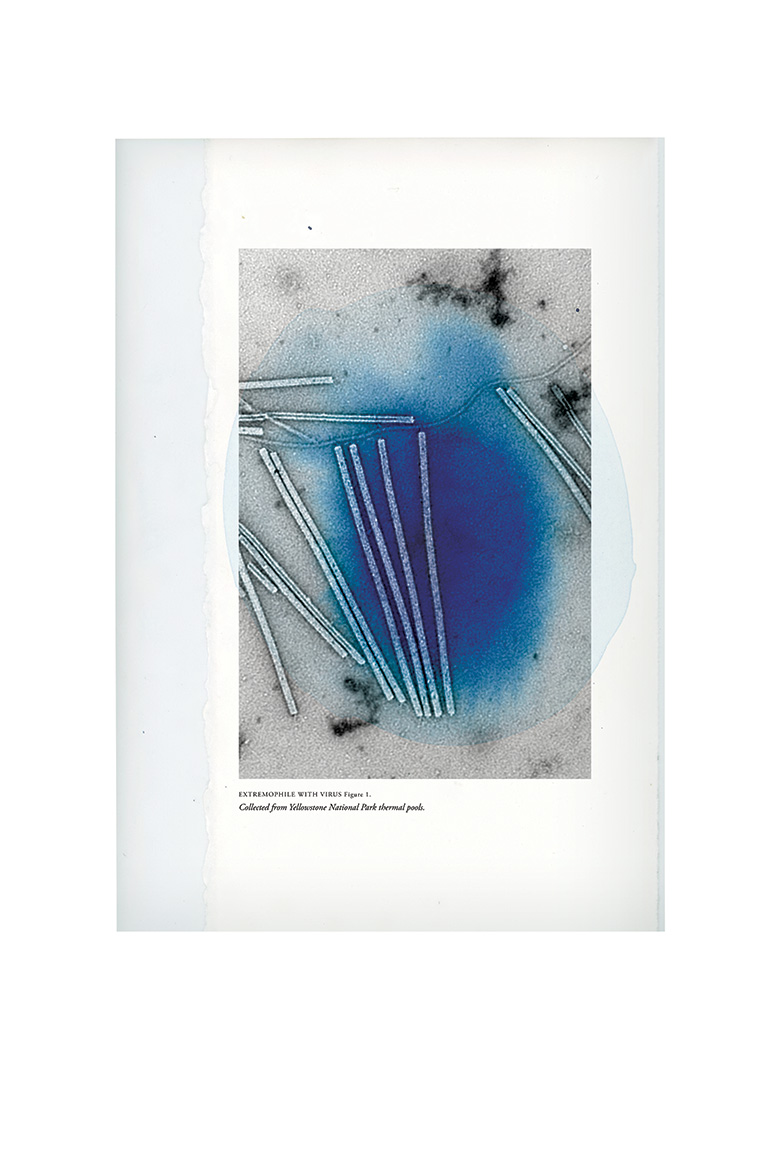

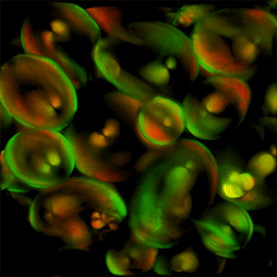

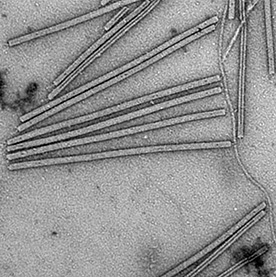

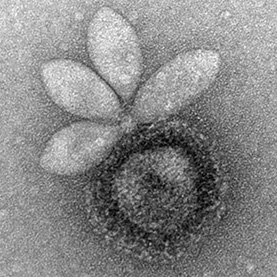

POOLS OF AVALON

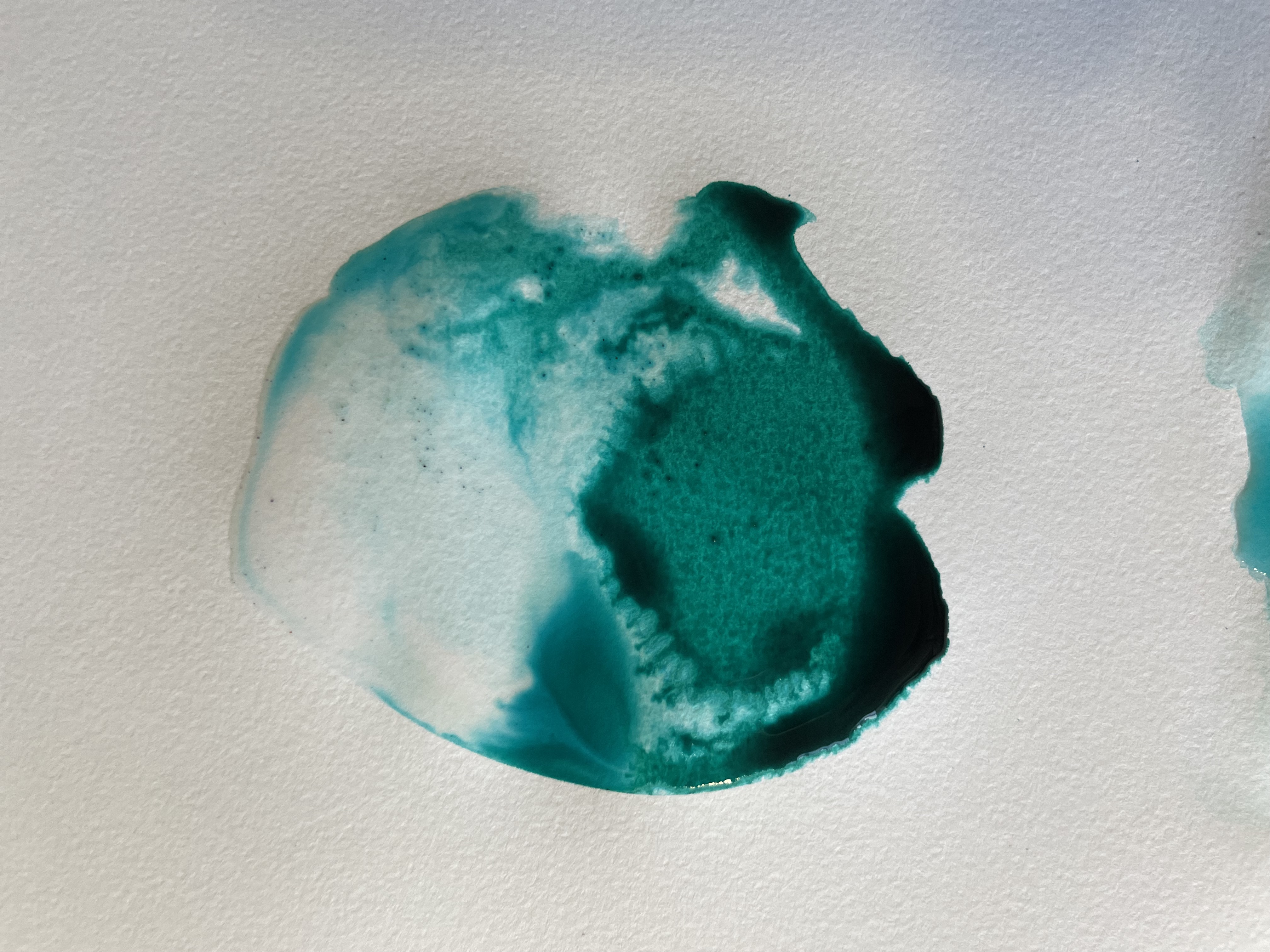

Imagine yourself immersed in a hot tub, except this isn’t an ordinary hot tub. It’s much hotter and filled with acid that’s eating away at everything. This nightmare is, in reality, heaven for microorganisms called Archaea, which were discovered in 1977 by a researcher named Carl R. Woese at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Although his discovery was initially met with hostility from the scientific community, it was eventually exalted as a turning point of how we view living organisms. Instead of taking for granted that all life belonged to either prokaryotes or eukaryotes, which include plants, animal, and fungi, Woese’s work showed that this new group of organisms was widespread across our planet, especially in extreme environments.

Hostile habitats like hot springs not only serve as homes but also as battlegrounds. Archaea have to contend with viruses that have co-evolved with them to hijack their resources. The three pieces show various viruses that scientists are currently investigating to understand how they interact with their hosts. The artist inked pools of color, which were inspired by the thermal basins at Yellowstone. It serves as a reminder that even under conditions that should be inhospitable, life longs for itself.

POOLS OF AVALON

Imagine yourself immersed in a hot tub, except this isn’t an ordinary hot tub. It’s much hotter and filled with acid that’s eating away at everything. This nightmare is, in reality, heaven for microorganisms called Archaea, which were discovered in 1977 by a researcher named Carl R. Woese at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Although his discovery was initially met with hostility from the scientific community, it was eventually exalted as a turning point of how we view living organisms. Instead of taking for granted that all life belonged to either prokaryotes or eukaryotes, which include plants, animal, and fungi, Woese’s work showed that this new group of organisms was widespread across our planet, especially in extreme environments.

Hostile habitats like hot springs not only serve as homes but also as battlegrounds. Archaea have to contend with viruses that have co-evolved with them to hijack their resources. The three pieces show various viruses that scientists are currently investigating to understand how they interact with their hosts. The artist inked pools of color, which were inspired by the thermal basins at Yellowstone. It serves as a reminder that even under conditions that should be inhospitable, life longs to be.

POOLS OF AVALON

Imagine yourself immersed in a hot tub, except this isn’t an ordinary hot tub. It’s much hotter and filled with acid that’s eating away at everything. This nightmare is, in reality, heaven for microorganisms called Archaea, which were discovered in 1977 by a researcher named Carl R. Woese at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Although his discovery was initially met with hostility from the scientific community, it was eventually exalted as a turning point of how we view living organisms. Instead of taking for granted that all life belonged to either prokaryotes or eukaryotes, which include plants, animal, and fungi, Woese’s work showed that this new group of organisms was widespread across our planet, especially in extreme environments.

Hostile habitats like hot springs not only serve as homes but also as battlegrounds. Archaea have to contend with viruses that have co-evolved with them to hijack their resources. The three pieces show various viruses that scientists are currently investigating to understand how they interact with their hosts. The artist inked pools of color, which were inspired by the thermal basins at Yellowstone. It serves as a reminder that even under conditions that should be inhospitable, life longs to be.

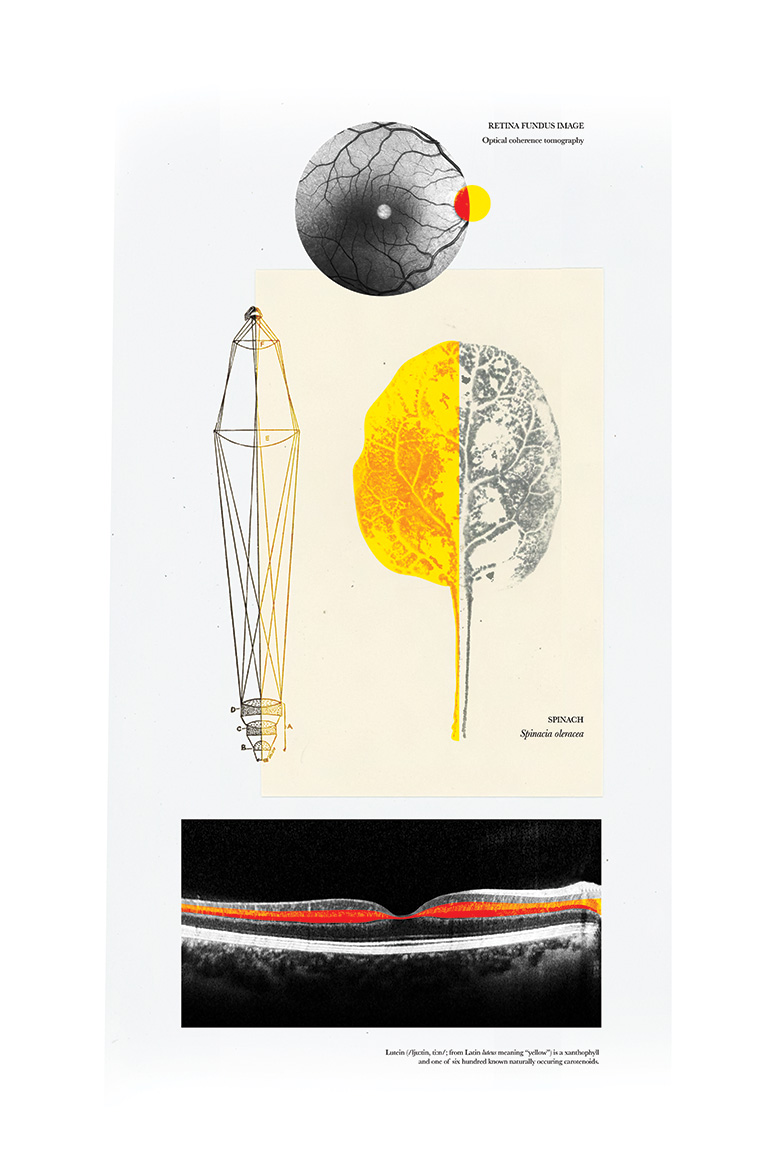

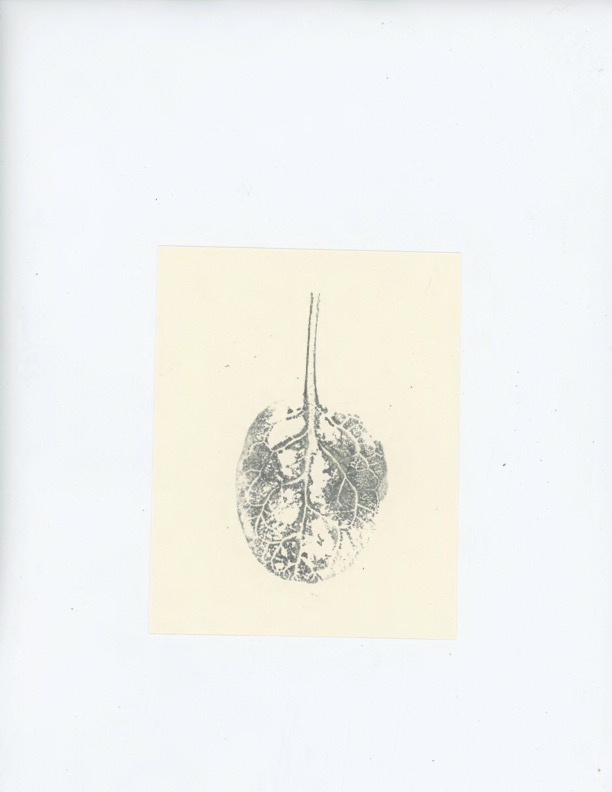

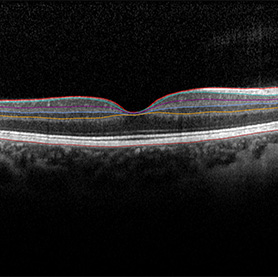

PROMINENCE

Perhaps one of the least surprising things about growing up is realizing that your mom was right about spinach. Somewhere between hating it as a child to devouring it in salads, you may have asked yourself– why bother? Most of us know about its magical properties through Popeye the Sailor Man who poured canned spinach down his throat to give his muscles a boost before a big fight. Although we may not reap the exact same benefit, we consume over 32 million tons of this plant globally, and for good reason. In addition to providing a panoply of vitamins, it also provides iron, calcium, and pigments that our body cannot make on its own.

One such pigment is lutein, a yellow-red chemical, which is found in the region of the eye responsible for color vision. Inspired by Francis Picabia’s Dada diagrams, the piece brings together retinal scans of lutein’s location in the eye, leaf prints of spinach, and diagrams of microscopy lenses. The resulting poster represents the anti-art movement of Dadaism and asks us to reconsider the world around us. What would it look like without colors? What makes something aesthetically pleasing? What is your definition of art?

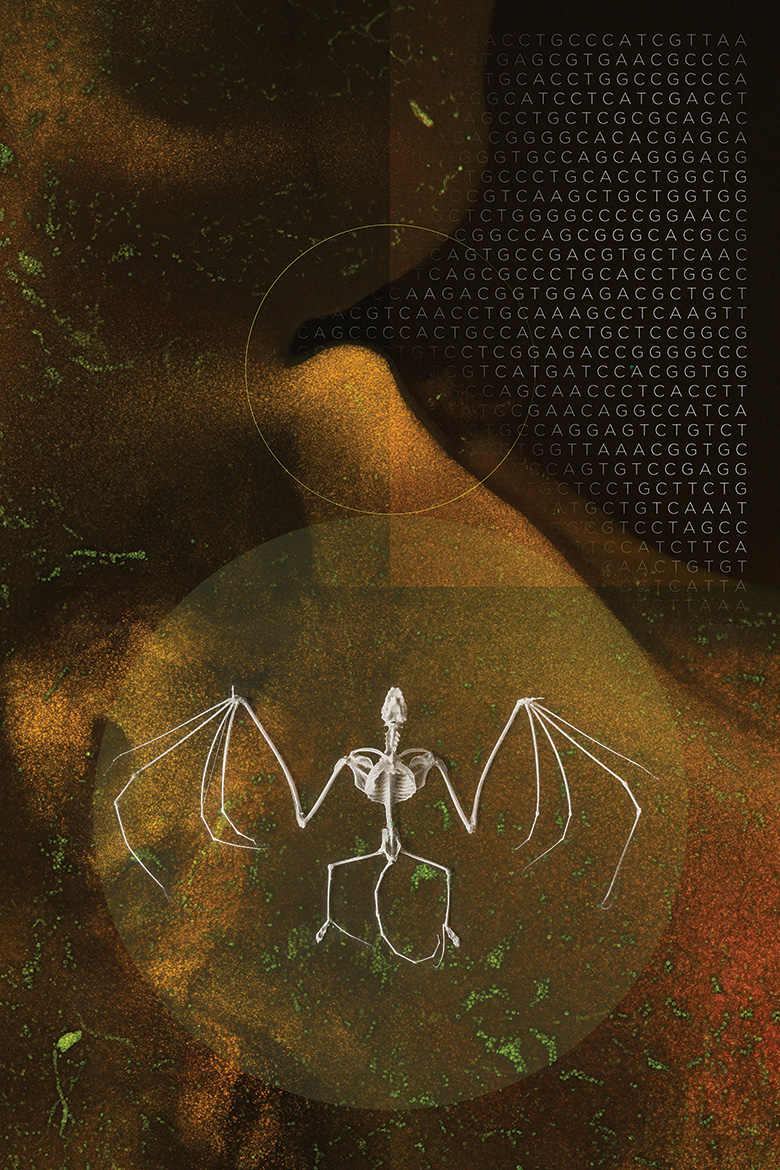

MAPPING NI’ HODIŁHIŁ

For most of us, bats symbolize sinister creatures that prowl in the dark to attack innocent victims. Such beliefs, however, are deeply unfair because bats confer innumerable benefits to their surroundings, including pollinating plants, distributing seeds that maintain forests, and providing pest control services. Rather than recoiling with fear and disgust when we see them fly across the skies, perhaps we should regard them as the Navajo did–as intermediaries that guard the night sky and bring us divine offerings.

Scientists have always been fascinated by bats because they are the only mammals that have achieved powered flight, allowing them to occupy diverse ecosystems. Intriguingly, their wing structures are not completely understood, even though fossil records have shown that they have been around for over 50 million years. Constructed from the images of genes that are important for the development of wing membranes in bats, their genetic sequences, and a bat skeleton, the image evokes a book cover for a science fiction story, prompting us to reconsider how we think about these fascinating creatures.

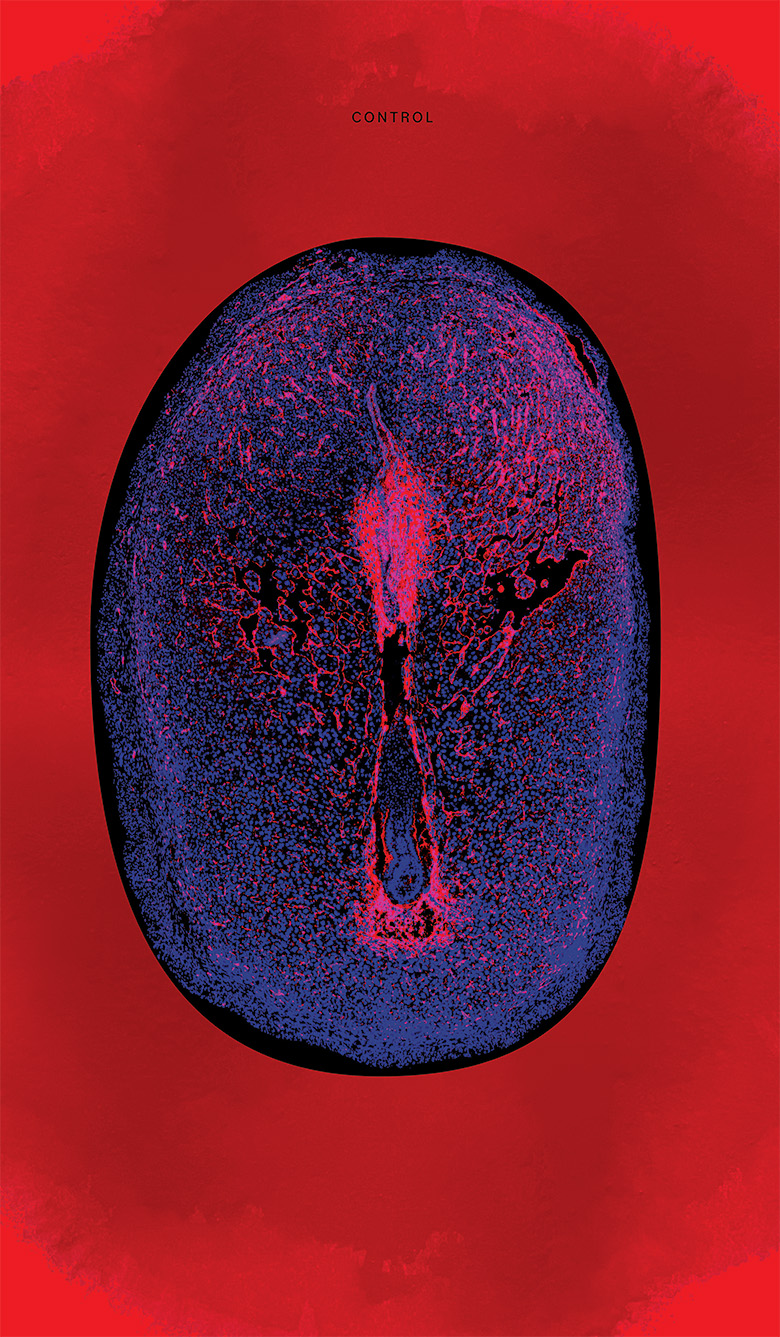

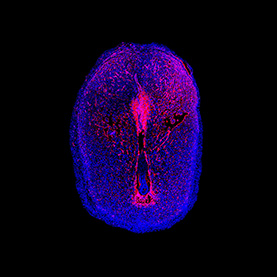

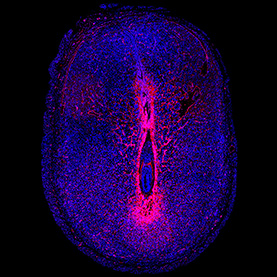

SEVERN STREAMS

Across the world and in all of its cultures, the gift of a child has been revered since time immemorial. From mere mortals to the gods, everyone has a person who brought them into the world. Although improvements in medicine have drastically reduced the complications associated with childbirth over the past centuries, several questions remain unanswered. Specifically, how do the chemicals associated with modern society influence our bodies and will they affect future generations?

Phthalates, specifically di-isononyl phthalates, are commonly found in plastic products such as storage containers, medical devices, fabrics, and toys. Concerningly, these chemicals break down in our body and can pass into the bloodstream, amniotic fluids, and breast milk. Although more studies are needed, researchers have conclusively shown that exposure to these chemicals can disrupt pregnancy and affect litter sizes in mice, underscoring the need to take a closer look at human pregnancies.

The banners have been created from data that compare tissue samples from pregnant mice that have been exposed to di-isononyl phthalates and those that have not. The background has been created as a visual extension of the data–the control has a deep-red ink stain to show the rich network of blood vessels while the phthalate-treated sample is washed out to mirror the decrease in blood vessels. The images serve as a reminder that although modernization solves many problems, it also creates novel ones.

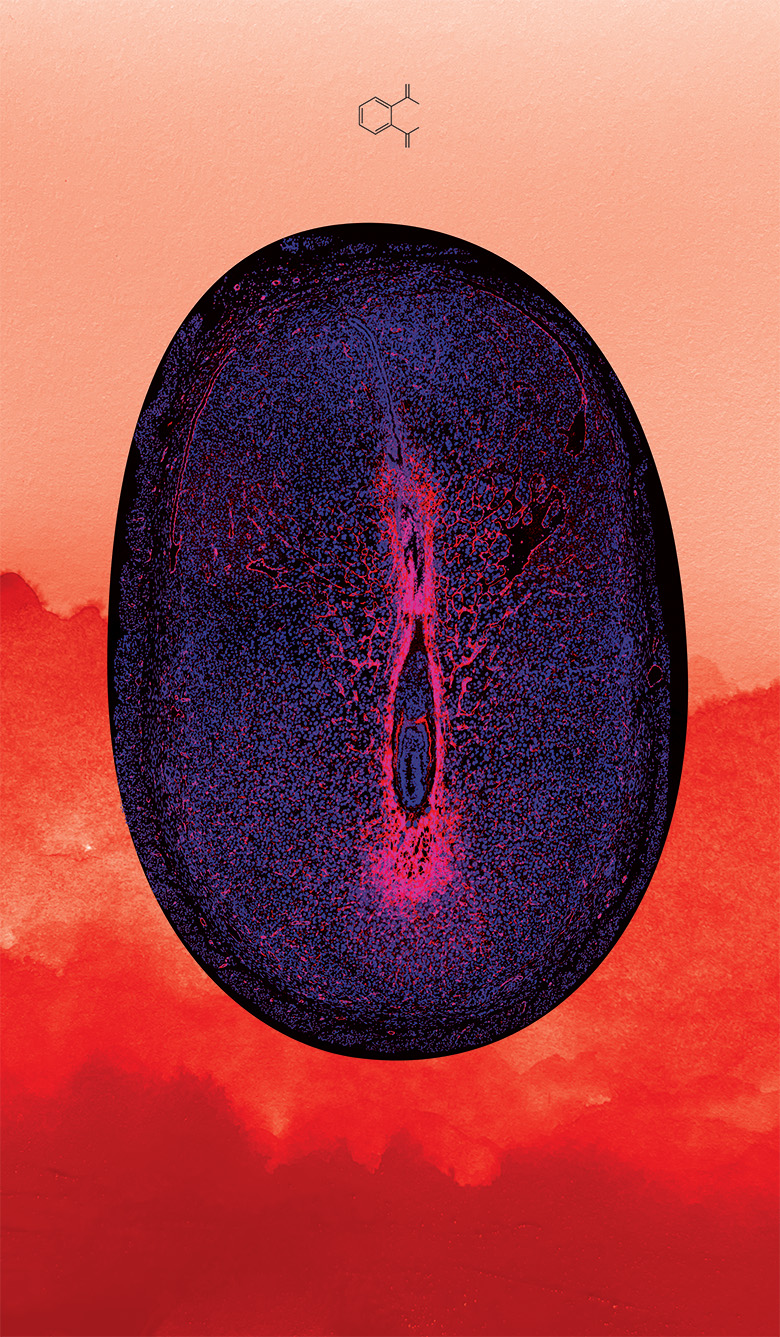

SEVERN STREAMS

Across the world and in all of its cultures, the gift of a child has been revered since time immemorial. From mere mortals to the gods, everyone has a person who brought them into the world. Although improvements in medicine have drastically reduced the complications associated with childbirth over the past centuries, several questions remain unanswered. Specifically, how do the chemicals associated with modern society influence our bodies and will they affect future generations?

Phthalates, specifically di-isononyl phthalates, are commonly found in plastic products such as storage containers, medical devices, fabrics, and toys. Concerningly, these chemicals break down in our body and can pass into the bloodstream, amniotic fluids, and breast milk. Although more studies are needed, researchers have conclusively shown that exposure to these chemicals can disrupt pregnancy and affect litter sizes in mice, underscoring the need to take a closer look at human pregnancies.

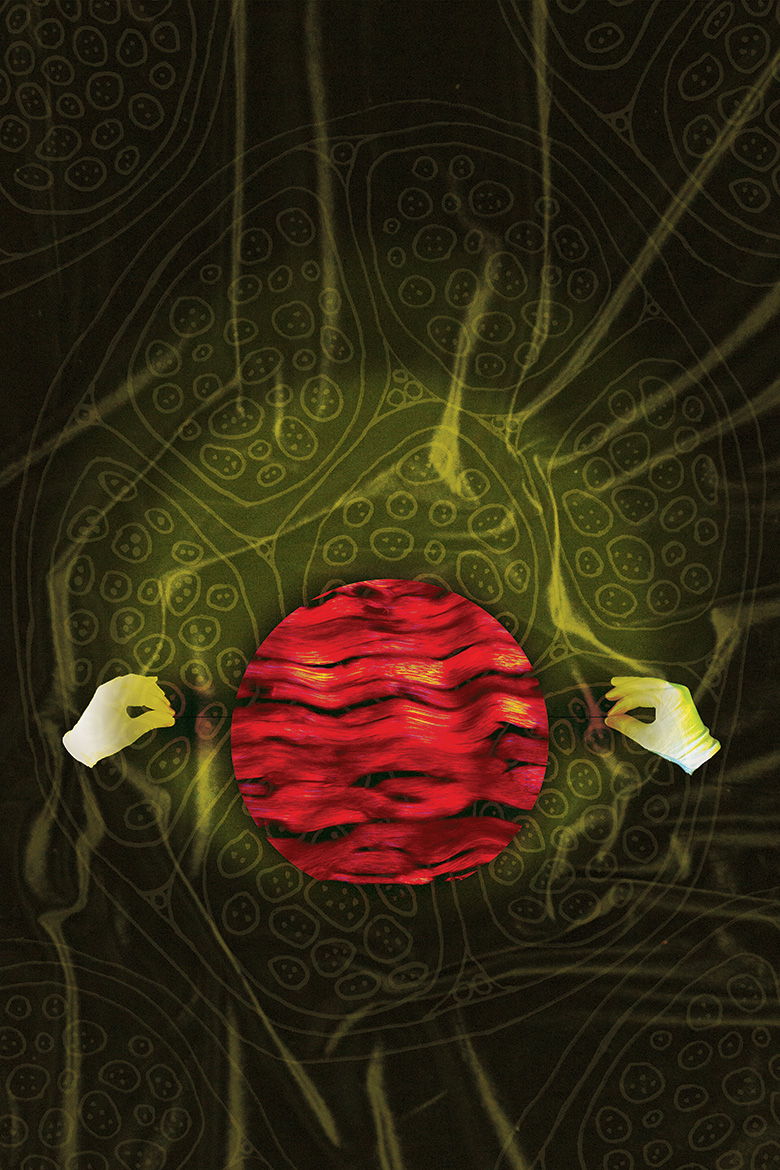

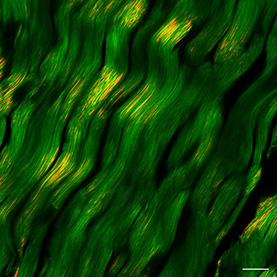

SHADOWBOXED

For over 2500 years, magic has captured people’s imaginations. It evolved from simple tricks to becoming associated with the occult, which led to the persecution of magicians. Over time, however, magic took over the big stage through the performances of Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin, who inspired Erik Weisz to change his name to Harry Houdini. While tales of these illusions are still captivating, we often forget that magic does not require a vast arena of breathless spectators. Often, it happens in a quiet corner where a solitary scientist is hunched over, perhaps peering through a microscope, and discovering something that changes our understanding of the world.

Through this piece, the artist wanted to capture that feeling of awe a researcher experiences when, for a brief period of time, they’re the only ones in the entire world who know one of Nature’s secrets. In the center of the piece lies collagen fibers in tendons, which are cords of strong tissues that attach muscles to bones. Researchers use these in stress tests to ask how diseases can affect soft tissues. Placing this image against a velvet background, flanked by the artist’s hands, confers a sense of mystery and showmanship. Listen closely as you inspect the image; you might hear it whisper “Abracadabra” as more details reveal themselves.

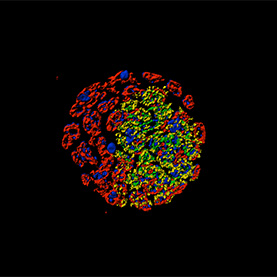

SKY OF DUSK IN ILLINOIS

The first few weeks of pregnancy juxtaposes a pregnant person who may not be aware of the life that is growing inside them and an embryo that is rapidly dividing while it travels to the uterus. Superficially, the first few stages of embryo development sound deceptively simple: one cell doubles over and over to form a ball of cells. Researchers, however, have found that the process involves an orchestra of cellular signals that have to be timed perfectly to create a fetus.

Unfortunately, this elegant mechanism can be derailed by phthalates, which are present all around us. One such chemical, diethylhexyl phthalate, is especially dangerous because it is similar to the hormones estrogen and progesterone that play key roles during pregnancy. Concerned by the prospect of rising infertility, scientists are now studying

how the cells talk to each other during embryonic development. As you study the piece, notice how the fetal cells grow against the dark background, which symbolizes the womb. The explosion of colored dots represents the symphony of growing life that can be easily disrupted by the discordant presence of plastics.

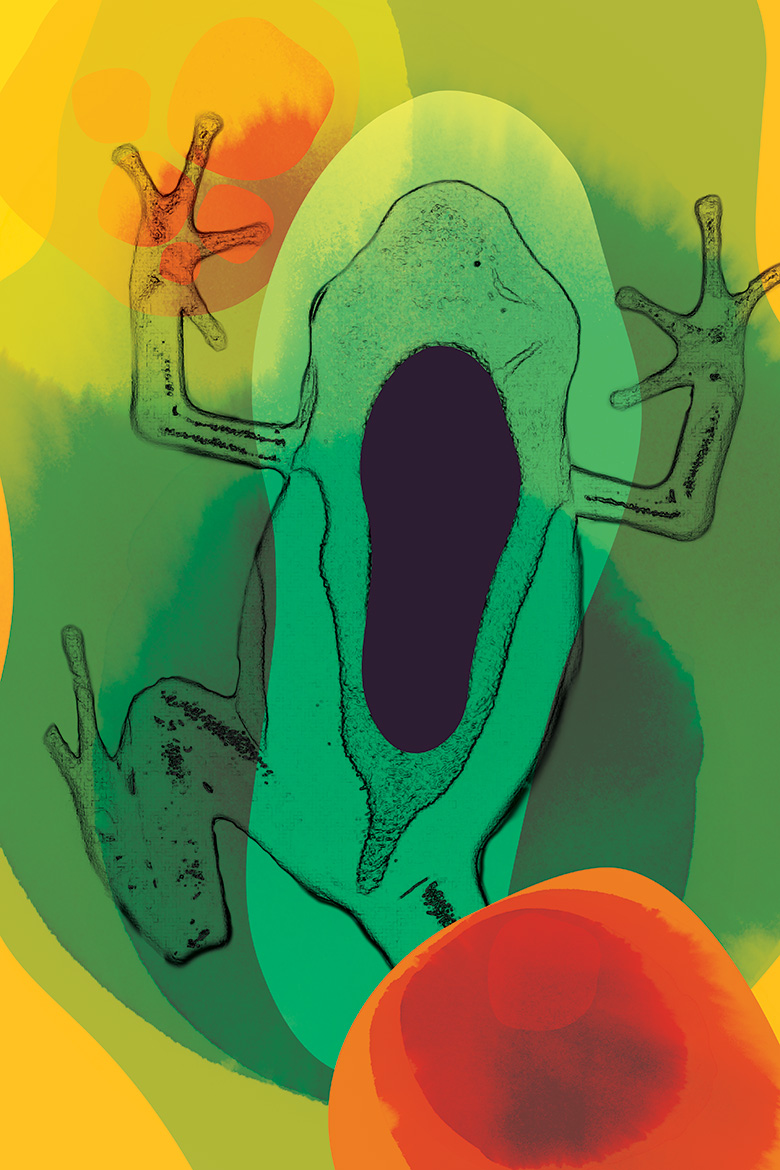

STORGECHROME

In biology, many animals use aposematism to warn predators that they are dangerous. The first warning involves the use of bright, high-contrast colors, including red, yellow, black, and white. If any animal is foolish enough to ignore these signs, the non-visible defenses teach them a lesson they’re unlikely to forget. Poison dart frogs are an example of this–their bright colors signal how toxic they are if consumed. These deadly creatures, however, harbor a loving heart that makes them wonderful parents.

Countless studies have shown that male poison dart frogs take excellent care of their eggs, ensuring that they are clean, hydrated, and safe from predators. Once the eggs hatch, the dads give piggyback rides to their tadpoles to help them reach pools of water. Moms also do their fair share, depending on the species. Parental care in frogs is an active area of research because they challenge conventional notions of what it means to be a parent. When male frogs disappear, for example, the females take over all the responsibilities without missing a beat, prompting questions about how their brains make the switch that, in turn, affects their behavior.

The pairing of the pieces reflect the loving relationship between frog parents and their embryos. Inspired by Helen Frankenthaler, an American abstract expressionist painter, and American printmaker Jules Olitski, the artist wanted to create images that can be used as clothing designs. The vibrant ink stains closely resemble different species of poison dart frogs and the patterns on the embryos have been created by mimicking the different patterns found on the parents, which help them recognize each other. Too often, our concept of gendered clothes remains within the confines of pink and blue. Through these pieces, the artist shows us that in the animal world, there is no such limitation. Bold is beautiful.

STORGECHROME

In biology, many animals use aposematism to warn predators that they are dangerous. The first warning involves the use of bright, high-contrast colors, including red, yellow, black, and white. If any animal is foolish enough to ignore these signs, the non-visible defenses teach them a lesson they’re unlikely to forget. Poison dart frogs are an example of this–their bright colors signal how toxic they are if consumed. These deadly creatures, however, harbor a loving heart that makes them wonderful parents.

Countless studies have shown that male poison dart frogs take excellent care of their eggs, ensuring that they are clean, hydrated, and safe from predators. Once the eggs hatch, the dads give piggyback rides to their tadpoles to help them reach pools of water. Moms also do their fair share, depending on the species. Parental care in frogs is an active area of research because they challenge conventional notions of what it means to be a parent. When male frogs disappear, for example, the females take over all the responsibilities without missing a beat, prompting questions about how their brains make the switch that, in turn, affects their behavior.

The pairing of the pieces reflect the loving relationship between frog parents and their embryos. Inspired by Helen Frankenthaler, an American abstract expressionist painter, and American printmaker Jules Olitski, the artist wanted to create images that can be used as clothing designs. The vibrant ink stains closely resemble different species of poison dart frogs and the patterns on the embryos have been created by mimicking the different patterns found on the parents, which help them recognize each other. Too often, our concept of gendered clothes remains within the confines of pink and blue. Through these pieces, the artist shows us that in the animal world, there is no such limitation. Bold is beautiful.

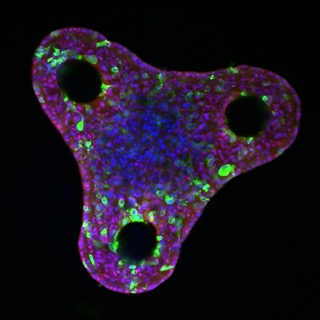

THE EYE OF A NEEDLE

In geometry, “Squaring the Circle” is a problem that was first proposed in Greek mathematics. The challenge was to construct a square which has the same area as a given circle by only using a ruler and compass. For over four millenia, mathematicians tried and failed to solve this question, and in 1882 the task was proven to be impossible because of the complex nature of the number pi. Consequently, the expression “squaring the circle” has become a metaphor for attempting something that cannot be accomplished.

The artist addresses this mathematical conundrum by drawing inspiration from liver studies because it is the only organ in the human body that can do the impossible–it can regenerate almost completely after being damaged. Scientists are now trying to understand what factors affect liver development to create better models for liver disease. The fidget- spinner shapes are slices of a growing liver that have been stained in red, blue, and green. The background has been created by adding photographs that the artist took of the recent solar eclipse. Taken together, the piece represents hope in the face of an insurmountable challenge.

Scientist Collaborator

Miranda O’Dell

Instrument

Nanozoomer Slide Scanner

Funding Agency

IGB Core Facilities Group

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Umnia Doha and Duncan Nall

Instrument

Multiphoton Confocal Microscope Zeiss 710 with Mai Tai eHP Ti:sapphire laser

Funding Agency

IGB Core Facilities Group

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Miranda O’Dell

Instrument

Nanozoomer Slide Scanner

Funding Agency

IGB Core Facilities Group

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Erinn Dady, Esther Ngumbi Group

Instrument

DSLR

Funding Agency

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Erinn Dady, Esther Ngumbi Group

Instrument

DSLR

Funding Agency

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Shelby Lawson, Mark Hauber, Janice Enos, and Sharon Gill

Mark Hauber Group

Instrument

DSLR

Funding Agency

National Science Foundation, National Geographic, American Ornithological

Society, Illinois Ornithological Society

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Changyi Zhang and Catherine Koterba

Whitaker Group

Instrument

Transmission electron microscopy

Funding Agency

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Changyi Zhang and Catherine Koterba

Whitaker Group

Instrument

Transmission electron microscopy

Funding Agency

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Changyi Zhang and Catherine Koterba

Whitaker Group

Instrument

Transmission electron microscopy

Funding Agency

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Corinne Campbell and Naiman Khan

Instrument

Heidelberg Engineering OCT SPECTRALIS

Funding Agency

Hass Avocado Board, University of Illinois, and the Egg Nutrition Center

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Daniel Urban

Instrument

Zeiss LSM 700 Confocal - four laser point scanning confocal with a single pinhole

Funding Agency

NSF

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Indrani C Bagchi and Arpita Bhurke

Instrument

Zeiss Axiovert 200M with the Apotome

Funding Agency

NIH

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Indrani C Bagchi and Arpita Bhurke

Instrument

Zeiss Axiovert 200M with the Apotome

Funding Agency

NIH

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Mahmuda Arshee

Instrument

Multiphoton Confocal Microscope Zeiss 710 with Mai Tai eHP Ti:sapphire laser

Funding Agency

Burroughs Wellcome Fund

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Lyda Yuliana Parra Forero

Instrument

Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan - six laser point scanning confocal with Airyscan

Funding Agency

NIH

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Eva K Fischer, Sarah E Westrick, Jen B Moss, and Katie Julkowski

Instrument

DSLR

Funding Agency

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the NSF

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Eva K Fischer, Sarah E Westrick, Jen B Moss, and Katie Julkowski

Instrument

DSLR

Funding Agency

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the NSF

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Scientist Collaborator

Brock Grenci and Allison Paxhia

Instrument

Zeiss LSM 700 Confocal - four laser point scanning confocal with a single pinhole

Funding Agency

Funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Original Imaging

Special Thanks

Nelson family and BodyWork Associates; Matt Cho and Cafeteria and Company; Special thanks to the eclipse photography of Mickey Mangan

Image Rights

Images not for public use without permission from the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology

Special Thanks

Champaign businessman Doug Nelson, President of BodyWork Associates, first proposed the idea that became Art of Science, and his continued efforts to support the exhibit made its realization possible. The IGB is also grateful to James Barham of Barham Benefit Group and [co][lab] founder Matt Cho for hosting the annual exhibit.